The coral reef and the rainforest are the most diverse marine and terrestrial ecosystems, respectively. They both represent what seems on the surface a paradox—nutrient poor soils in the rainforest and nutrient poor waters in the reef, despite the incredible diversity of organisms in each place. Coral reefs actually rely on the low nutrient density of the water, because when there are more nutrients available, algae tends to outcompete corals. In the rainforest, the nutrient poor soils are due to the rapid nutrient cycling and wide diversity of decomposers facilitated by high temperatures and rainfall and necessary for the incredible growth present there. In addition, my taxon groups in the rainforest and on the reef were somewhat parallel: the trees in the forest and the corals on the reef. Each of these is the foundation of the ecosystem, photosynthesize (or have a symbiotic relationship with photosynthesizing organisms), and are incredibly abundant.

I took the wide diversity of each species as a challenge, and tried to identify as many as I could, although in each case some of the organisms looked incredibly similar to one another and occupied similar niches.

Unfortunately, when I set out to take this course, I saw the obstacle of my food allergies first and any academic challenges second. The result of this was that I was thoroughly prepared to avoid food allergens, and less prepared for the actual coursework. Despite this, I learned more in these two weeks than I think I ever have in two weeks before in my life: about the rainforest, the reef, and research in the field. Interestingly (maybe this is TMI) I have a skin condition and thought it would get worse on the trip. It did the opposite and flared up as soon as we returned to Houston. Allergies also turned out to be easy to deal with, as the cooks on the island and in the rainforest were very careful and had limited ingredients in the kitchen to begin with (fewer contaminants).

It’s hard to choose a favorite part of the course. We saw spider monkeys shaking trees at us to get us to go away (we just thought they were cute); a tapir on one of our camera traps (we all cheered!), scarlet macaws almost every day in the rainforest, the inside of a leafcutter ant nest. I think the most intriguing things I saw were zombie ants. Zombie ants are ants that are infected with a fungus that somehow compels the ant to climb up (in this case on a palm). The ant then clings to the inside of the palm and slowly dies as the fungus eats it from the inside out, then sends out a fruiting body (mushroom). We saw several of these, and some ants that were still moving but appeared lost on the bottom of palm leaves, possibly controlled by the fungus. The phenomenon is incredible and frightening, as when I’ve related it to friends and family one of the first questions they ask is “can that infect humans?!” The answer to that question is no. At least, no known fungus will do that to humans.

In addition to the course content, I think we all learned how to split up the work to get something done, and not obsess about the details (for those of us inclined to do so). For example, the first research project we did took all day to analyze. We spent the morning making sure each morphospecies (“species” identified as “species A” based on observable characteristics when the species name is unimportant) was carefully identified, and the entire afternoon making a poster. We had all of our graphs on a laptop instead of the poster itself, and had the one person with some of the best handwriting and drawing skills (Liz) draw the entire poster (no printing facilities in the jungle!). By the end of the two weeks, we could whip up a poster in a few hours, max. A few people would work on each section, and at least two people would write and draw on the poster. We were much more efficient, and still conveyed our work effectively.

Scott requested a species count for each taxon in the reflection post, so here those are:

Trees

Elephant Ear/ Guanacaste (Enterlobium cyclocarpum)

Trumpet tree (Cecropia peltata)

Caribbean Pine (Pinus caribaea)

Rosewood (Dalbergia stevensonii)

Billy Webb (Sweetia panamensis)

Nargusta (Terminalia amazonica)

Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla)

Spanish Cedar (Cedrela odorata)

Bull Thorn Acacia / Bullhorn Acacia (Acacia/Vachellia cornigera)

Basket Tie-Tie (Desmonicus schippii)

Banana (Musa sapientum/paradisiaca)

Prickly Yellow (Zanthoxylum sp.)

White Poisonwood (Sebastiana tuerckheimiana)

Black Poisonwood (Metopium Browneii) (Tropical Education Center)

Fiddlewood (Vitex gaumeri)

Kapik/Ceiba (Ceiba pentandra)

Horse’s Balls Tree (Stemmadenia donnell-smithii)

Guava (Psidium guajava)

White oak sp. (Quercus insignis) (Tropical Education Center)

Sapodilla/Chicle (Manilhara zapota)

Give-and-Take Palm (Crysophila staurocantha)

Gumbolimbo/ Tourist Tree (Bursera simaruba)

Jobillo (Astronium graveolens)

Bay Cedar (Guazuma ulmifolia)

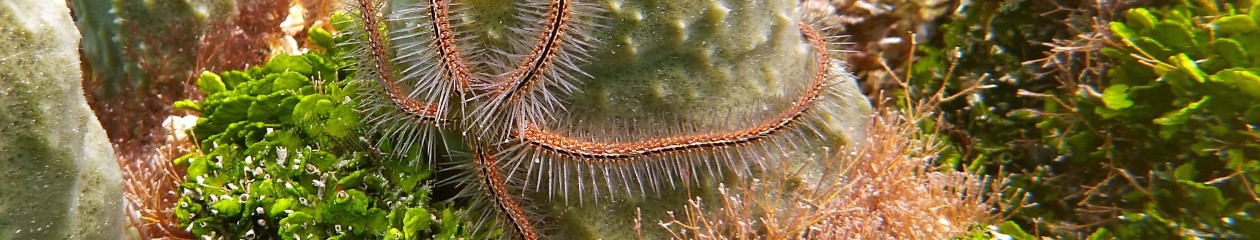

Corals

Elkhorn Coral (Acropora palmata)

Staghorn Coral (Acropora cervicornis)

Mustard Hill Coral (Porites astreoides)

Thin Finger Coral (Porites divaricata)

Grooved Brain Coral (Pseudodiploria labyrinthiformis)

Boulder Brain Coral (Colpophyllia natans)

Pillar Coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus)

Symmetrical Brain Coral (Pseudodiploria strigosa)

Golfball Coral (Favia fragum)

Lettuce Coral (Agaricia sp.)

Mountainous Star Coral (Orbicella faveolata)

Massive Starlet Coral (Siderastrea siderea)

Additional Siderastrea sp., maybe stellata, dead coral

Boulder Star Coral (Montastrea cavernosa)