I want (an it is required of me) to recount the three most memorable experiences from this course. The first is obvious, and that is the experience of meeting and getting to know the incredible group of instructors and students who decided it was important or even necessary to complete this course. Most people would not consider trudging a dozen miles in the Chiquibul or collecting marine debris at Glover’s Atoll to be an entirely pleasant way to spend one’s summer. Each and every participant made it their aim, however, to not just complete these and other challenges, but to take away from them a positive message. Not to mention the positivity and diligence of the workers at each of the two field sites we stayed at. These people have devoted their life to the cause of conservation and biological research and to the education of young people like myself. In five years, I am confident I will still remember the attitudes and moments of courage from those who inspired me during the last two weeks. This was undoubtably my favorite part of the course.

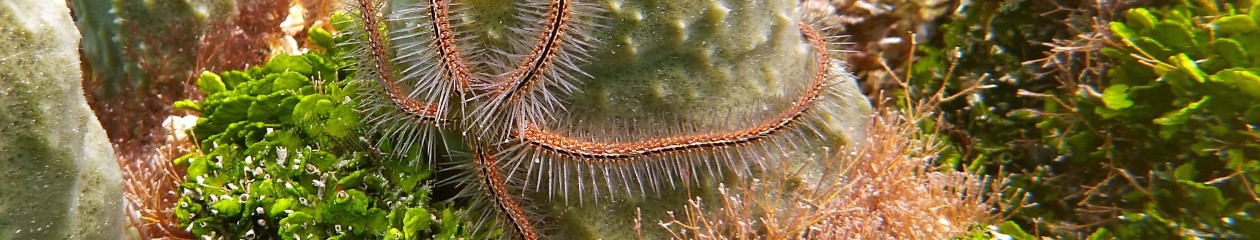

Secondly, I will never forget the peace of mind that comes with field work. Never before had I reached a feeling of calm as when diving to the bottom of a reef, hearing nothing but my own air bubbles, and carefully observing and recording the diversity of life I saw. The same is true of my time spent in the Chiquibul, where the cacophony of noise reaches a transcendental hum. In the field, your eyes and ears become attuned to each stimulus they encounter. Over time, nothing slips by and you can appreciate everything around you. I dream of a time in my life where I can spend months or even years in this blissful state. I guess this experience has given me a dragon to chase, my first taste of “field euphoria.” I take it back, you guys were great, but this was undoubtably my favorite part of the course.

The third memorable aspect of this trip (and reducing this trip to just three memories does not really do it justice) was the unstoppable stream of information coming from both qualitatively observing and directly quantifying my surroundings. Both from direct observation and methodical quantifying I became more attune to the biotic and abiotic processes occurring all around me. But comfort in your assertions about this environment are short-lived because of the astounding amount of alternate information popping up left and right. When we conducted studies of different biological systems we constantly faced the dilemma of what question to ask (what data to quantify), because there are a million valid questions, but many fewer that actually lead to meaningful results. Even once you have asked the right question, it is not always clear how to interpret the data you have collected. Different statistical methods can lead to finding wildly different conclusions from the same data set. This experience has taught me that specific knowledge of life is key to understanding the problems that face our modern world. It has also taught me that careful scrutiny and painstaking attention to detail is the only way to sift through this wealth of information and acquire relevant knowledge. The daunting feeling that comes with this realization could be viewed negatively (as my least favorite realization) but as always understanding what you are up against can make it feel less scary. So overall, a net positive experience.

How can I most succinctly summarize this experience and still do it justice? One adjective that comes to mind immediately is educational. EBIO319 is hands down the most educational experience I have had in my time at Rice. You can read and discuss all you want and begin to understand the systems of organisms that exist in the tropics, but until you see them first hand it is near impossible to fully appreciate their novelty and complexity. My expectations of adventure were certainly met, but I had no idea how much knowledge I could attain from exploring these pristine habitats.

Moreover, the nature of this experience was paramountly thought-provoking—stimulating connections each time we reached a new location and inspected its life forms. One of the first lectures in the Chiquibul focused on life in the rainforest canopy. It touched on the paradoxical duality of high biodiversity existing in soils without highly abundant nutrients. This concept immediately rang a bell in my head because it was so connected to one of the fundamental aspects of my lecture topic from the reef. On coral reefs, waters are oligotrophic as well and yet support a similar richness and abundance of life. Both ecosystems rely on the cycling of nutrients from the top of the ecosystem to the bottom and back again from the bottom to the top. In the rainforest, decomposers like microorganisms, fungi, roaches, and other insects recycle plant and animal detritus which then can be absorbed by roots. These lucky roots (along with the beating tropical sun) support the growth of tall trees that host the larger heterotrophs which ultimately (along with plants) become food for those detritivores I mentioned before.

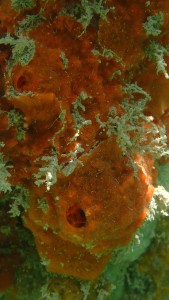

On the reef this process is more cryptic, since it prominently features microbes. Here highly abundant and productive autotrophic bacteria photosynthetically fix carbon within their cells. Along with dead microbes and larger organisms, the exuded photosynthates from these bacteria become food for heterotrophic bacteria, abundant in the water column and more so on the reef benthos. This cycle of nutrients is so tightly linked that nutrients hardly exist free floating in the water for long. Larger organisms filter feed on these nutritious microbes, grow, and are then consumed themselves by ever larger organisms. All eventually die and become food for the heterotrophic bacteria that form the base of this microbial loop.

Belize is truly a biodiversity hotspot. A center for conservation focused research and legislation that promotes the sustainability of such an environment. What we have in both of these locations in Belize is ideal specialization in an ideal habitat. Nothing goes to waste. Every necessary niche is filled by a diversity of life. This is only possible when anthropogenic extinction is limited and preservation is the top priority.