DAY 6 — I think I’m starting to get used to waking up early and walking outside to feel the ocean breeze. This morning it was less of a breeze and more of a strong wind. It’s hard to belize that tomorrow is our last full day on the island.

This morning we had more delicious homemade bread and mixed fruit for breakfast. By 8:15 we were headed to the snorkel shack. Today we went to the northern back reef to collect a sampling of the diverse organisms in the reef (and seagrass) habitat. We walked through some adorable baby mangroves and trudged through some squishy seagrass beds to get to the patch reefs.

I saw a spotted eel (Gymnothorax moringa), the Caribbean giant anemone (Condylactis gigantea), Halimeda chips, and a couple brittle stars. I also saw a LOT of fish, including the juvenile Gray Angelfish (Pomacanthus arcuatus), the intermediate stage French Angelfish (Pomacanthus paru), the Bluehead (Thalassoma bifasciatum), the Rock Beauty (Holacanthus tricolor), and the French Grunt (Haemulon favolineatum).

PHOTO OF SPOTTED EEL

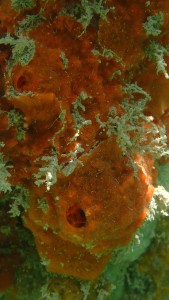

We swam our loot back to Middle Caye and sorted everything in the wet lab troughs. For good reason, we weren’t allowed to collect any sponges, so my taxonomic group was lacking. I did still have the dead sponge from yesterday, which I identified as a Yellow Tube Sponge (Aplysina fistularis).

PHOTO OF DEAD SPONGE

Some cool organisms collected were the Cocoa Damselfish (Stegastes variabilis), the Caribbean Giant Anemone (Condylactis gigantea), a fire worm (Heimodic carcunculata), and a Manta Shrimp (Pseudosquilla cilicate).

We managed to collect a tiny baby octopus (named Squishy) who became a fast favorite among the TFBs and highlight of the day. Squishy was hiding in a Diadema antillarum inked when the Cocoa damselfish lunged towards her (or him), which was extra cute. We think Squishy was an Octopus briareus.

PHOTO OF SQUISHY

After lunch Ellie, Deepu, and Anna gave their presentations on herbivorous fish, piscivorous fish, and invasive species, respectively. It was the perfect day for these lectures, as I had just seen a bunch of fish in the patch reef area.

After lectures we returned our collected friends to the ocean from whence they came and began analyzing our marine debris data from yesterday. We produced a poster (which got rave reviews) showing that plastic was both the most abundant type of marine debris by number of pieces and by weight.

Tomorrow, whether the weather be fair or whether the weather be not, we’ll weather the weather, whatever the weather, whether we like it or not. Meaning: we are going out to enjoy ourselves around various parts of the atoll, even if it stays windy.