2:31 am

- Lily: ZZZzzzzZZZZZZZZzzzz

- Howler monkey: HUWAOOOO (the phonetic spelling of howler monkey calls)

- Lily: *wakes up halfway*

3:48 am

- Lily: zzzzzzzzzzzz

- Howler money: HUWAOOOO, HUWAOOOO, HUWAOOOO

- Lily: *puts pillow over head*

4:?? am

- Howler monkey: HUWAOOOO

- Lily: ……

IMG_0298 (Video of Howler Monkey Calls, taken by Sam – 05/21/25)

We’re in the howler monkey’s territory. In fact, an adorable family of howler monkeys roams these grounds. Last night, they claimed the tree next to our cabin for the night and made it known. When we woke up and saw the baby hanging by its tail in the tree, we forgave the family instantly for the few nighttime disturbances. We spent our pre-breakfast birding session watching the monkeys feast on some leaves instead.

We had an eventful day ahead – exploring caves, analyzing our pee traps, and hiking uphill to catch the sunset. After breakfast, we took a quick stroll to the cave across from our cabin (we’re living on top of a cave network), filled with cultural remnants and cool geological formations. As we ventured in, the bright, green, warmth of the rainforest quickly changed to damp, cool, stillness, with dripping water and flitters of bats from above. The landscape in front of us looked like an alien planet. The cave floor was filled with muddy grooves and slimy, translucent, blob-shaped masses (stalactites). They’re so blobby they almost look like they’re a living creature. The ceiling, on the other hand, had bell-shaped holes and icicle-shaped masses (stalagmites). Stalactites and stalagmites form when acidic water from the ground above dissolves the limestone of the walls and deposits the calcium carbonate precipitate (https://sciencenotes.org/stalagmites-and-stalactites-how-they-form-and-more/). Although we couldn’t venture far (access was restricted by the research station to protect the cultural ruins within), it was incredible to see a new pocket of the world and the nature within.

(Stalagmites and Stalactites – livescience.com)

Post-class group pic in our caving helmets, we geared up for the rainforest right above. The most important piece of gear we needed was tube caps. Today was the day we collected our pitfall (pee) traps, and we definitely preferred having lids on our vials filled with a mix of urine and insects. The retrieval process went fairly quickly, and we even saw an epiphyte arrowhead plant on the way back! Dr. Evans was able to identify it after I discussed it in my epiphyte taxonomy presentation the day before.

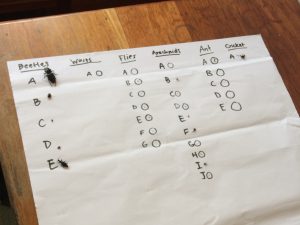

Upon reaching the lab, I realized my pee tube had been dripping. But the spill was totally worth it because the nitrogen in my pee (or its location) might have successfully attracted a blueberry-sized grasshopper into my tube. After compiling all class data, we found that the tubes buried on the forest floor had the greatest number of organisms and species, suggesting that there is a greater availability of nitrogen on the forest floor than on the canopy. This was a super cool mini-study (a pilot study) to better understand our test system and data trends to see if we want to continue the project on a greater scale.

Feeling proud of our project’s success, we regained the energy to hike up a steep, winding trail to the top of one of the rolling hills for a peaceful, glorious sunset. When we reached the hilltop panting, drenched in sweat, and chugging water, we breathed. The sun was just beginning to set, and rays were peeking in through the canopy. We climbed the ladder up the bird-watching tower, and once we reached the top, our view was rolling green hills as far as the eye could see. We took turns getting “golden hour” pics up on the deck and then took moments to breathe in the sounds and beauty of the jungle. I couldn’t think of a better bonding experience.

(Dr. Solomon Takes on Bird Tower – 05/21/25)

Hiking back in the dark, we were buzzing (like the insects) with excitement and eager to put our recently developed field biology skills into practice. We passed around cicada skins to wear as matching accessories, ate some carrot-flavored termites, tapped on trees to check for ant inhabitants, chased after neon-green glow-in-the-dark Click beetles, and even spotted upon the entrance to another cave system. The day unfolded like a nature-themed sandwich with caves at both ends and layers of discovery about organisms and their habitats in between.

Peace,

Lily 🙂

Today was full of adventure, from swimming into a sacred cave to spotting wildlife under the stars. We left Las Cuevas early and made our way to the Tropical Education Center, but not before stopping at the famous ATM (Actun Tunichil Muknal) cave. Getting inside meant swimming through the entrance and squeezing through narrow rock passages. It was intense but completely worth it—I loved every minute.

Today was full of adventure, from swimming into a sacred cave to spotting wildlife under the stars. We left Las Cuevas early and made our way to the Tropical Education Center, but not before stopping at the famous ATM (Actun Tunichil Muknal) cave. Getting inside meant swimming through the entrance and squeezing through narrow rock passages. It was intense but completely worth it—I loved every minute.