Now that I’m back from the trip and have sort of acclimated to the A/C blasting in my house, it’s time for some wrapping up and a heartfelt reflection! (Also, happy World Rainforest Day!)

One similarity between tropical rainforests and coral reefs is that they are both nutrient poor ecosystems but are also hotspots of biodiversity, and the methods of survival in these harsh conditions fuel biological diversity. For instance, coral reefs are microbially driven ecosystems because microorganisms retain and recycle nutrients for use by the coral organism. Microbial interactions with the holobiont whole can vary widely based on the coral species, symbiont clade and composition, and abiotic factors like light and temperature. Therefore, the diversity of the nutrient-recycling microbial community as a part of the holobiont promotes coral diversity. Additionally, trees and plants in tropical rainforests have adapted to the nutrient poor soils by displaying a variety of nutrient-maximizing methods. One example is buttress roots in trees. These roots spread horizontally under the soil (as opposed to downward vertically) in order to take advantage of the newly deposited nutrients in the upper layers of soil and store them in their plant tissue. These buttress roots also stabilize the tree by having thick, outward stretches at the bottom of the tree, and this also maximizes the amount of surface area the tree has with the most nutrient-rich top soil layers. Just like microorganisms for corals, phenotypic variations like buttress roots in tropical trees promote biodiversity driven by the need to maximize nutrient capturing abilities.

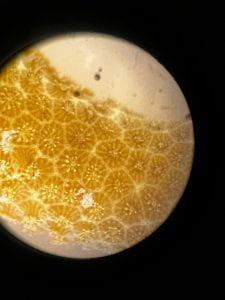

Another similarity between these two ecosystems is the competition for light between organisms. In coral reefs and tropical rainforests, light is a limited and highly coveted commodity. One way that coral organisms ensure access to enough like is through phenotypic plasticity. When a coral of a certain species is present in light-limited conditions, it can be phenotypically different from a coral of the same species in conditions with ample light. The phenotypic form of corals in low light levels is plating, where the coral grows outward in flat plates to maximize the surface area exposed to light so that its dinoflagellate symbionts can photosynthesize and provide nutrients (this also ties back to the lack of nutrients!). The drive for phenotypic forms that maximize light access also fuel coral biodiversity. In tropical rainforests, the thick canopy is an example of the strong competition for light. Tree branches grow outward and create a dense mat of canopy vegetation where almost every sliver of space in the sunlight is taken up by plant life. This leads to tough competition on the forest floor, where organisms better suited to low light conditions compete for the little light transmitting to them. Epiphytes are an example of how this competition within and under the canopy for light has led to biological diversity. Epiphytes are non-parasitic plants that grow upon other plants. They are often seen growing on the trunks and branches of trees. This ability to grow vertically higher than the ground floor is an adaptation to limited light, where epiphytes can advantageously grow closer to the canopy and avoid the competition and overgrowth in the understory. For both of these ecosystems, competition for sunlight drives biodiversity.

One similarity between the two ecosystems that I have personally observed is the 3-D topography. When snorkeling on the fore reef, I got to see the massive spur and groove structure of the coral reef. When hiking the bird tower trail in particular, I experienced the large changes in elevation of the tropical rainforest. Another similarity that I observed is the ability of organisms to occupy even the smallest of spaces and niches. On the reef, I saw this in urchins hiding in crevices and rubble, zoanthids covering tube sponges in tiny polyps, and benthic sea cucumbers underneath structures. In the forest, I saw this in snakes eating frog eggs in trees, spiders with webs in the stalactites of a cave, and a Mexican burrowing toad inhabiting an abandoned leafcutter ant nest.

I have also noticed differences between the two ecosystems, and the major difference is how apparent the impact of destructive forces are. From my personal observations, I saw that destruction was more obvious in the reef than in the forest. While snorkeling, it was so clear to see the expanses of coral rubble, evidence of coral death from disease or bleaching, and impacts of overfishing (in non-MPA reefs). The degradation of the reefs was easy to spot. However, I found it less easy to spot the effects of destructive forces in the rainforest. Of course, the trails and roads and clearings are evidence of human landscape degradation, but outside of this, proof of degradation was not as obvious as it is in the coral reefs. Of course, seeing Morelet’s tree frogs that are critically endangered and scarlet macaws that are endangered in Belize brought the destruction of the tropical forest ecosystem and its organisms to the forefront of our minds, but it was not as if we were seeing dead stretches of forest while conducting our research.

This course completely exceeded my expectations. I did not expect to learn so much about Belizean culture and history, and I was definitely surprised by how much I enjoyed the fieldwork in both ecosystems. I also did not expect to make so many meaningful connections and friendships with my fellow TFBs. Going into this course, I expected to do the things listed on the schedule, but I did not expect to learn as much as I did from those things and for these experiences to have as much of an impact on my ideas for my future career as they did. I did not expect to come out of the trip as the McKenna that I am today with my new revelations and interests, but I am endlessly grateful that I did!

My favorite parts of the course were definitely those with fieldwork! Although the conditions were rough (washing machine currents, accidental fire coral collisions, and mosquitos / chiggers, extreme slopes to hike, and torrential downpours), I thoroughly enjoyed the day-in-the-life moments of being TFB, physical labor included! I also loved the food! I already miss Belizean food; I looked forward to every meal everyday and always felt replenished. My ultimate favorite part of the course was the people! The Belize Babes, Surf & Turf, the two smallest TFBs, the Glovers staff, Ruth and Claudios, the LCRS staff, I feel so lucky to have met and spent time with all of these people! I loved learning alongside the Babes and under the direction and motivating encouragement of Surf and Turf. Everyone I met in Belize was so hospitable and dedicated to ensuring that I enjoy my stay, and it was amazing to learn from these people too and their knowledge and experiences!

My least favorite part of the course was probably the bugs. However, my collection of bites are well-earned TFB battle scars! I also found it hard to get enough time day to day to fill out my field notebook, but after a few days I learned how to maximize my time so that I wouldn’t fall behind (as much as possible). Overall, I really enjoyed this course and didn’t have a big problem with anything; everything about this course qualifies as a “favorite” of mine, just some things are less favorited than others.

The biggest thing that I learned that I think will define where I take my future is my passion for (and my apparent skill for) science communication. I learned that I love talking about and communicating sciency things, and I was told that I’m easy to listen to when doing so. This has inspired me to pursue a future in communicating science! This course also opened my eyes to the complications of wildlife/ecosystem protection. Hearing from the marine safety officers and the Belize Fisheries Department taught me the difficulties of actually enforcing the regulations and restrictions of MPAs. Additionally, hearing from Rafael and Dario about the recent problem of poaching around LCRS made it clear that without the ability to fully surveil a protected area, even forest reserves can fall victim to destructive forces. It really helped me understand the intricacies that must be considered alongside an area’s label as being protected. By far, the most surprising thing that I learned during this course was what lionfish tastes like! I never in my life thought that I would have the opportunity to eat lionfish (especially in ceviche), but that experience will definitely not be forgotten.

This course/trip has been inexplicably elucidating on so many levels. I can’t thank everyone enough for this opportunity, and I already cherish these moments in memory. Belize holds a special place in my heart! Cheers to the end of an un-Belize-able experience and to the beginning of my travel fever and science communication career aspirations!

– McKenna