I’ve learned a lot in the past two weeks, and now that I’ve had a couple days to digest the trip and reflect, I feel like I’m ready to share my main takeaways from the trip. We spent a lot of time observing both the rainforest and the reef ecosystem, and I feel like one of my first key takeaways was that there are a number of similarities which might contribute to them both being such vibrant, biodiverse ecosystems.

The first of these key similarities is the number of mutualisms and beneficial species interactions going on in each ecosystem. In the rainforest, we learned about and observed the relationship between cecropia trees and Azteca ants, but that is far from the only mutualism present or the only mutualism we observed. It isn’t even the only mutualism we observed involving ants: the leafcutter ants are also engaged in a mutualism with the fungus they cultivate. Similarly, the basis of the reef ecosystem is the coral, but that coral gets its nutrients through a mutualism with zooxanthellae algae. Although many ecosystems see different species interacting, I think the density of mutualistic relationships in rainforest and reef ecosystems is unique.

Another similarity which surprised me was the nutrient limitation in both ecosystems. This surprised me to learn about both times. These ecosystems, which seem so rich, are both operating on extremely nutrient-poor substrates. The trick, in both, is that the biomass is holding nutrients and that nutrients are being cycled incredibly quickly. This was hard to observe, but we saw the byproducts: lush vegetation, towering trees, complex corals. We also were exposed to some of the factors which lead to the high rate of cycling, like the heat and humidity. It was interesting that both ecosystems are limited in this way, and yet both have such high levels of biodiversity.

A final link I wanted to touch on was the vulnerability of both ecosystems. The rainforest and the reef are both under threat due to a number of anthropomorphic challenges. We learned about how climate change impacts them both and how illegal poaching and the pet trade harm biodiversity. We also heard about (and saw, firsthand, in our trash pickup and elsewhere) how pollution can impact both ecosystems. All in all, the loss of these crucial habitats due to human activities was something that came up time and time again and is something that’s a huge issue. High levels of biological diversity mean that these ecosystems are particularly vulnerable because many of the species present are specialized and vulnerable to changes.

I will say, although there were many similarities between the rainforest and the reef, it did feel like the wildlife was much more accessible in the reef ecosystem. Maybe they’re less hidden, or maybe they’re less scared of people, but it felt like we were much more lucky in seeing interesting fish and other creatures on the reef than in seeing creatures in the rainforest.

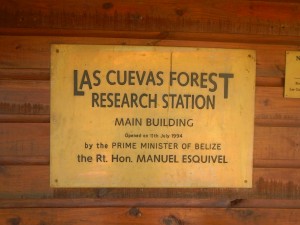

I was so fortunate to be able to go to Belize and make these observations for myself. This course exceeded my expectations and was able to surprise me at every turn. One thing I was pleasantly surprised by was the way we carried out scientific experiments and explorations from beginning to end, starting with the design process and going all the way to drawing conclusions and presenting them. I had the impression that, given time constraints, we would be given set procedures and carry them out, maybe not even analyzing our results. I was amazed by the end of the trip when we would be given a general topic and design a whole experiment around it, carrying it out and making a poster by the end of the day. It really was a great crash course in the process of science. I also was surprised at how manageable the physical elements of the trip were. It’s either a testament to how the course was structured—in that we built up to the harder parts—or I was just more in shape than I thought. My initial fears were unfounded in that regard. I also want to shout out the food—I hadn’t expected it to be such a great part of the trip. Even the lodging was exceeded my expectations—I think being told to bring a sleeping bag made me think we would be in much more rugged conditions, but they were actually great!

There were some things about the trip which were more difficult for me, or which I didn’t like as much. Although the snorkeling was super beautiful and it was interesting to learn about the reef, I think overall it might not be for me. It was stressful for me to be out in open water, even close to a boat, and I think that I might not be built for hours of snorkeling. Given the opportunity, I definitely would go out again for short stints as a tourist, but I wouldn’t make a career out of it, if that makes sense.

It’s difficult to narrow my takeaways from this experience down to just three key lessons. If I had to, I think the first thing I’ll remember from this trip is the nutrient limitation of both rainforests and reefs. That surprised me so much that I don’t think I’ll ever forget it. Such vibrant ecosystems, and the soil and seabed are so limited. I don’t think that ever occurred to me as a possibility. Another key takeaway is the fact that these ecosystems are under threat. It’s so tragic that such incredible ecosystems are so vulnerable, but it only reinforces the fact that we need to do something now to protect them. Finally, I think the last key thing I’ll remember from this trip is that science is a collaborative exercise and can be incredibly fun and rewarding if carried out together. There were so many things I would never have realized if someone hadn’t been there to connect a key link or point out something I had missed. I think I knew, on an academic level, that we were meant to do research collaboratively, but this trip cemented it for me. The ease with which our group settled into a rhythm and a good working groove just showed how essential cooperation and collaboration is.

I’m so glad I had this experience, and I’m glad you’ve been along for the ride. I’ll sign off with some of my favorite photos from the experience: